“Don’t buy upgrades, ride up grades””

On 1 July 1903, Henri Desgranges organized a publicity stunt aimed at selling more newspapers. This event was to be the most grueling endurance race in the world and featured 60 “working class” riders competing in a competition simply known as “The Tour” or The Tour de France (TdF).

Eddy Merckx averaged 23.7 mph (38.1kph) during his 1971 TdF victory while riding a 21.1-lb (9.6kg) steel frame bike, without clipless pedals (they wouldn’t be invented for another 13 years). In 2004, Lance Armstrong averaged 25.1 mph (40.5 kph), all while riding a 14.99-lb (6.8kg) carbon fiber bicycle, clipless pedals, Dura-Ace STI shifting system, and of course, the full-power of performance-enhancing drugs (PEDS).

So what’s the point?

In Lance Armstrong’s own words, “It’s not about the bike.” Tim Declercq, who finished the 2021 Tour de France in 141st place averaged 23.7 mph, the exact same speed as Eddy Merckx, 50 years prior.

Trek 5500 bicycle used by Lance Armstrong in the 2000 Tour de France (Image Source: Smithsonian).

Professional Bike Fitting

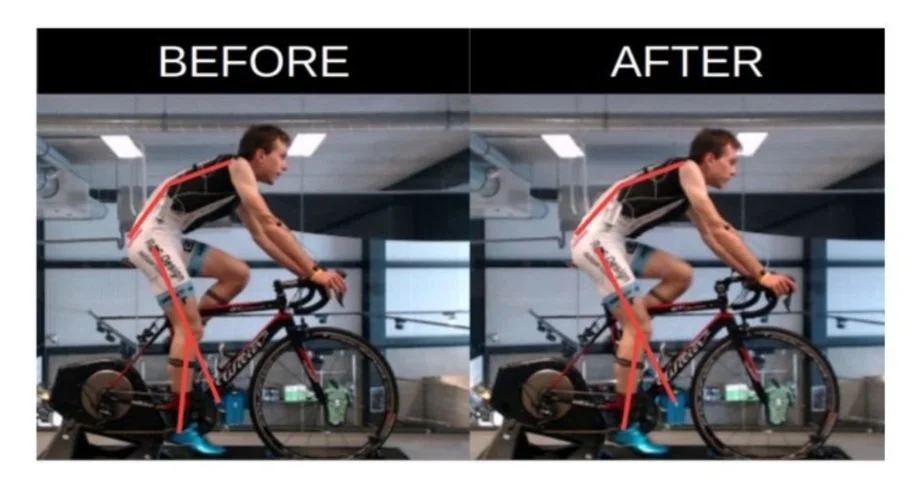

Bike Fitting is the process of making adjustments to the bike until your optimal riding position is reached. A bike fit is a compromise between comfort, performance, and injury prevention. Trying to adapt your body to your bike vs adjusting your bike’s settings (saddle height, seat tilt, setback, handlebar height, reach, etc.) to your unique body not only makes you faster but also makes riding more comfortable and reduces over-use injuries.

A pro cyclist will adjust their bike for performance and speed, whereas a recreational commuter will set up theirs for comfort.

How do I know if I need a bike fitting?

If you can reach the ground flat-footed while seated then it’s time for a proper bike-fitting

Painful knees?

Pain in your back?

Butt or saddle discomfort?

Your out-of-shape riding buddies are faster than you?

Just riding with your saddle a couple of inches too low can reduce your pedal power by 80%

You’re a regular rider but have not gotten much faster?

Pain in hands?

Neck hurting?

Hot spots in your feet?

Slow cornering (due to improper weight distribution)??

How your bike is adjusted (bikefit) affects how your bicycle performs and where your weight is distributed, which affects braking, turning, handling, and pedaling power/efficiency. 3D dynamic BikeFittings are expensive, but no worries, we offer a DIY Professional Bike Fitting for only $37, or stop in your local bike shop for instruction.

Total distance covered and average speed of the winners of the Tour de France (1903–2011). Interruptions are the 2 periods of noncelebration due to World Wars I and II (1915–1918 and 1940–1946). The fastest wins of the Tour de France’s great dominators (≥5 victories) are also shown: cyclist’s name, year (speed in km/h).

Image Source & Quote: Santalla, Alfredo, et al. “The Tour de France: An Updated Physiological Review.” International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, vol. 7, no. 3, Sept. 2012, pp. 200–209.

Chain Lubricant

Think this chain needs some lube?? (Image Source: Flickr)

Roller chains in laboratory settings are 97 to 99% efficient. However, in the real world, bike chains are exposed to all the elements, debris, bad weather, and dirty roads, which is why in reality, they don’t even operate at 75% efficiency. A superior chain lubricant will add 10 - 20+ watts of power due to insanely low coefficients of friction and an ability to suspend dirt particles away from the drive-train components.

You can spend hundreds of dollars just to shave off a couple of ounces, or you could just spend $27 to get the World’s fastest wet lube and let your chain operate optimally and defy Mother Nature’s wishes.

Chain lubricant doesn’t do much good if you are just applying lube to a dirty chain. A clean machine is a fast and reliable machine. Nothing wears down bike components and reduces performance as much as a dirty bike. A dirty chain wears down the cogs making shifting more difficult, which wears down even more components.

Weigh Less: Power-To-Weight Ratio

“Models of cycling performance have suggested that a 1 kg increase in BW can increase cycling time up a 5% grade by∼1%” ”

Chris Fromme, 4 time Tour de France (TdF) winner, weighed 167 lbs (76kg) when he turned pro at 22, the following year he finished the TdF in 84th place.

Fromme started winning Tours after dropping 22 pounds, riding at 145-lbs (66 kilos), and subsequently increased his power/weight ratio by 10%, allowing him to attack hills with unmatched power. Fromme also is no shorty, standing 6 feet 1 (1.86m) nor was overweight at 167lbs, but nothing improves performance as much as increasing your power-to-weight ratio, and losing weight is the fastest path to it.

Tour De France Photo. Date: circa 1930

Weight loss is the best upgrade for both roadies and XC-MTB riders, regardless of budget. You could spend $10,000 on the latest carbon fiber bicycle, just to save a pound or two, or you can drop 10 pounds, save money, ride faster and further simply by eating less or better.

Bicycle manufacturers and marketers will try to convince you that rotational or wheel weight is somehow more important than total rider weight (including rider and gear), however, it doesn’t matter where the weight comes from. While it’s true that lighter wheels accelerate faster, they also slow down faster. The only way that energy is lost is when you brake.

Haakonssen et al. in a 2015 study published in the European Journal of Sports Science, said this about cycling performance and body weight:

By reducing non-functional mass and optimizing functional lean muscle and thus power output in relative terms, cyclists have the potential to improve their performance.

Total Bicycle Weight & Bodyweight

Total Bicycle Weight = rider (you) + gear + emergency parts/tools + snacks + water + cell phone + keys + the bike. All matter equally. For 99% of cyclists, the cheapest and most effective way to reduce Total Bicycle Weight is for you, the cyclist, to lose excess fat. The most dominant factor in Chris Fromme’s ascendance from elite cyclist to legend is best summed up by one number, -22lbs (10kg).

Final Thoughts

Eddy Merckx rode a 1971 Colnago Molteni on his way to his Tour de France victory that same year. This 21-lb bike predates clipless pedals, wind tunnel testing, aero apparel/components, carbon fiber, modern sports nutrition, and 21-century training techniques, yet even in 2021, he would still be fast enough to compete with the best.

There is a 100% chance that whatever bike you have now is way better than that 1971 Colnago Molteni from half a century ago. It’s not about the bike or the upgrades. Get yours dialed in through a proper bike fitting, keep it clean and optimally lubed, and go out there and ride.

Jesse is the Director of Pedal Chile and lives in La Patagonia. Jesse has a Master of Science in Health and Human Performance and is an avid MTBer. Jesse enjoys reading books, particularly non-fiction and academic studies. Favorite MTB trail? The singletrack on the active volcano in Chile.

Sources & References

Haakonssen, Eric C., et al. “Body Composition of Female Road and Track Endurance Cyclists: Normative Values and Typical Changes.” European Journal of Sport Science, vol. 16, no. 6, 14 Sept. 2015, pp. 645–653, 10.1080/17461391.2015.1084538.

Lucia, Alejandro, et al. “The Tour de France: A Physiological Review.” Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, vol. 13, no. 5, 26 Sept. 2003, pp. 275–283.

National Museum of American History. “Trek 5500 Bicycle Used by Lance Armstrong in the 2000 Tour de France.” Smithsonian Institution, www.si.edu/object/trek-5500-bicycle-used-lance-armstrong-2000-tour-de-france:nmah_1294955.

Santalla, Alfredo, et al. “The Tour de France: An Updated Physiological Review.” International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, vol. 7, no. 3, Sept. 2012, pp. 200–209, 10.1123/ijspp.7.3.200.

Scoz, Robson Dias, et al. “Discomfort, Pain and Fatigue Levels of 160 Cyclists after a Kinematic Bike-Fitting Method: An Experimental Study.” BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine, vol. 7, no. 3, 1 Aug. 2021, p. e001096.