“The plane passing through the highest points at the front and rear of the saddle can have a maximum angle of nine degrees from horizontal. ”

If you compete in Union Cycliste Internationale (UCI)-sanctioned or regulated races, as of January 1st, 2016, you are allowed a maximum saddle angle of 9° (±1°). This is quite a lot of wiggle room, especially considering that for years, the saddle couldn’t be tilted more than 3° and was unofficially known as the “flatness rule.”

So why did the UCI change the “flatness rule” in 2016?

According to the Clarification Guide of the UCI Technical Regulations manual:

"It is important to grant the rider sufficient freedom to allow a comfortable position to be adopted, reducing the pressure on the perineum, while avoiding any deviation through an excessively sloping saddle that could improve sporting performance to an unacceptable degree by the addition of a lumbar support."

Or to phrase it more simply, tilting your saddle down is more comfortable and easier on your back and groin in certain riding conditions:

Hills

Riding low in the drops

The best saddle angle for climbing is 5 - 15 degrees

- Level Terrain = Level Saddle (or close to it)

- 5% downward saddle tilt = 15% hill

- 10 to 15% forward saddle tilt = 30% climb

- Saddle tilted forward/down

The best saddle angle for climbing is a forward saddle tilt of 5 to 15°

uphill climbing & the “science”

No sport is as thoroughly studied as cycling.

It’s the easiest athletic activity to perform an in-depth analysis of and is also low-risk. Of all the modifications that can be made to a bike, the pedal has received the most attention, since it’s the link between the rider and machine, and how we transfer our energy into motion.

Uphill bicycling, however, remains one of the least examined, mainly because inclines add a bunch of complexities to the research methodology. Then add in saddle angle to the mix, which until recently was a non-factor in elite competition, and what you get is “limited” valid research.

With that said, after combing through the data, I was able to find enough research to come to a few solid conclusions.

So, what does the “science” say about uphill climbing and saddle angle?

This is what a 20º/36% hill looks like (see picture below)

Muscle activation and coordination patterns are altered at around a 5-degree slope (a 5°/9% slope is not really steep…..I’d call it modestly steep)

Level or flat saddle angles become uncomfortable at around 5-degree slope and become increasingly more uncomfortable as it gets steeper

Changing your saddle angle will improve your climbing ability and comfort when hills become steep, frequent, or are long in distance.

Low back pain is common and is worsened from altering your posture during uphill bicycling (cycling uphill with a level saddle places more stress on your lumbar)

Riding posture & uphill cycling

When you are mountain biking or cycling uphill, you naturally change your posture by moving forward on the saddle and leaning forward. There are two main reasons for this:

To avoid lifting the front wheel off the ground

To keep a stable saddle position (not sliding off the seat)

Once you make these two positional modifications, you now changed the length-force ratio of your muscles, thus altering your pedaling mechanics and muscle activation patterns.

Steep hills (12°slope, minimum), modify the timing and duration of muscle activation, especially your quads and hamstrings.

Quads become less powerful

Hamstrings become more involved and work about 10% harder

Calves also are significantly more involved

Mountain biking: Climbing & saddle tilt

Climbing up steep singletrack is even tougher than climbing on the road.

A mountain biker needs to control and balance their MTB while navigating uneven and narrow terrain, all while simultaneously:

Keeping enough weight on the back tire for traction

Preventing the front wheel from lifting

Climbing over roots, rocks, logs, etc.

Looking out for fellow riders or hikers (unless it’s a unidirectional trail)

Watching for wildlife

This is why mountain bikes usually have a more slack seat tube angle (Pedal Chile article on STA) which places more weight over the rear tire and makes technical sections easier.

Altering Saddle angle & climbing

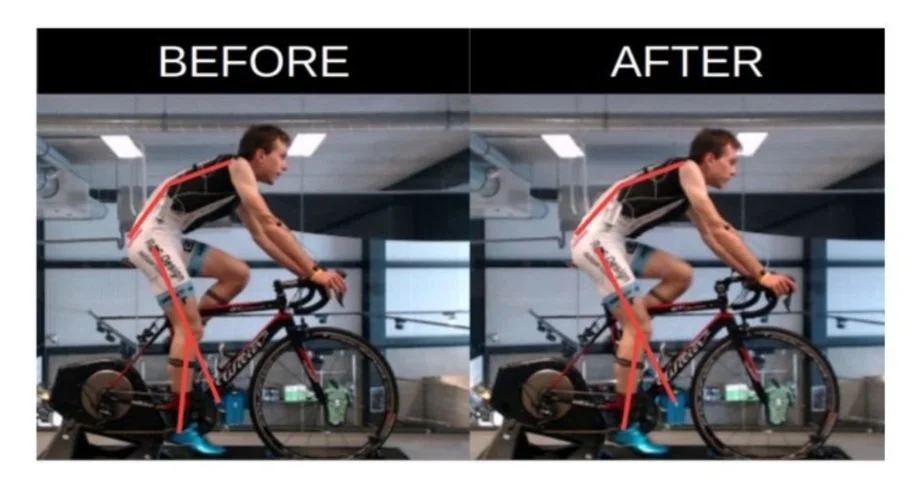

Tilted saddle = improved climbing performance

Altering the angle of the saddle, to coincide with the steepness of the hill will offset nearly all of your muscular and pedal stroke changes

You want to change the angle of your saddle to bring your posture as close to the posture you have during level riding

Tilted saddle = improved comfort

The steeper the slope the more you change your posture and lean forward, which decreases the area of the seat you are actually sitting on. This means your saddle loses all of its ergonomic characteristics, causing you to experience discomfort. Aligning the saddle with the slope will bring back the ergonomic benefits and comfort to that of flat riding.

Climbing: Why your saddle is not comfortable

Moving forward on your saddle while simultaneously leaning forward means you are sitting on the nose of the saddle with the majority of your weight. This compresses the front perineum and will cause pain in the groin area for both men and women.

Sitting on nose of seat = lots of weight on your “private parts”

Back pain: uphill Cycling & saddle angle

“Take home message: Low back pain is common among cyclists, regardless of age, gender, or type of bicycle. Its incidence and severity can be reduced by adjusting the saddle to introduce a 10–15° anterior inclination”

There are many possible bike-fit mechanisms for back pain in cyclists, such as:

Saddle height

Handlebar height

Reach

Saddle angle

Frame size

Saddle type

Length of cranks

Gearing

Cadence

Bicycle-style

Of all those reasons, saddle angle predominates, specifically while climbing or riding in the drops……combine this with mashing on big gears for miles, and you just pedaled up a recipe for back pain and saddle discomfort.

Saddle angle and manufacture designs

“Your Trek bicycle is designed for the seat to be level with the ground. Use a bubble level placed length-wise (front-to-back) on your seat for the best result.”

The majority of saddles are designed by the manufacturer to be ridden level with the ground. If you plan on tilting your seat, find a saddle that is designed to be angled by more than just a few degrees.

Final thought

The perfect saddle not only goes up and down but also tilts forward and back (plus lightweight & durable). Unless you have this magical seat, it’s best to bring an Allen key. Matching your saddle angle to the terrain is key to improving comfort, enjoyment, and performance.

For example, if you are tackling a long climb to ride epic singletrack, start by tilting your saddle down 5 to 15 degrees. Once at the top, return the nose of the saddle to level, or even a smidgen higher, as this will allow you to grip the saddle for fast descents and cornering.

Did you know you can cycle faster and climb easier, just by switching to Pedaling Science’s chain lubricant??

Jesse is the Director of Pedal Chile and lives in Chile’s Patagonia. Jesse has a Master of Science in Health & Human Performance and a Bachelor of Science in Kinesiology. Hobbies: Mountain biking, bicycle commuting, snowboarding, reading, taster of craft beers, and researcher.

More articles from Pedal Chile

Sources & references

“Researchers have reported that it is possible to improve cycling performance via kinesiology by adjusting both the rider and the bike”

Caddy, Oliver and Timmis, Matthew A. and Gordon, Dan (2016) Effects of saddle angle on heavy intensity time trial cycling: Implications of the UCI rule 1.3.014. Journal of Science and Cycling, 5 (1).pp. 18-25.

Fonda, Borut & Sarabon, Nejc. (2010). Inter-muscular coordination during uphill cycling in a seated position: a pilot study. Kinesiologia Slovenica. 16. 12-17.

Rodseth, M, and A Stewart. “Factors Associated with Lumbo-Pelvic Pain in Recreational Cyclists.” South African Journal of Sports Medicine, vol. 29, no. 1, 24 Oct. 2017, pp. 1–8, 10.17159/2078-516x/2017/v29i1a4239.

Salai, M., et al. “Effect of Changing the Saddle Angle on the Incidence of Low Back Pain in Recreational Bicyclists.” British Journal of Sports Medicine, vol. 33, no. 6, 1 Dec. 1999, pp. 398–400, 10.1136/bjsm.33.6.398.

Schultz, Samantha J, and Susan J Gordon. “Recreational cyclists: The relationship between low back pain and training characteristics.” International journal of exercise science vol. 3,3 79-85. 15 Jul. 2010

Silva, Gabriel, et al. “Comparative Analysis of Angles and Movements Associated with Sporting Gestures in Road Cyclists.” The Open Sports Medicine Journal, vol. 8, no. 1, 11 July 2014, pp. 23–27.

Stefanucci, Jeanine K., et al. “Distances Appear Different on Hills.” Perception & Psychophysics, vol. 67, no. 6, Aug. 2005, pp. 1052–1060, 10.3758/bf03193631.

Union Cycliste Internationale. CLARIFICATION GUIDE OF THE UCI TECHNICAL REGULATION. 10 Jan. 2020.