Here are some tips to improve your climbing, without the cliche/typical advice of “ride more,” “inflate tires,” “stay hydrated” or “stiffen the shocks.”

1) Increase your power-to-weight ratio (PWR)

Nothing will improve your climbing ability as much, or quickly, as improving your Power to Weight Ratio (PWR). In road cycling and mountain biking, the riders with the greatest PWR can pedal up hills the fastest.

There are 4 primary ways you can increase your PWR:

Lose weight (fat)

Gain strength (without gaining much weight)

Get a lighter bike/components (least improvement of the 4)

Lighten the load in your pack

For every half-mile (.8 km) slope at a ~15% gradient, each extra kilogram (2.2 lbs) of weight adds 6 seconds to the climb.

This means that for a cyclist who is 10 pounds overweight, while wearing a backpack weighing an additional 10 pounds, this will slow down the rider by nearly one-minute for every 1/2 mile or 880 yards.

Now, these figures are calculated based upon road cyclists, which means that they will be magnified while climbing single-track, as the variable terrain and obstacles make climbing, even slower.

Here a few examples of items that weigh about a kilogram (2.2 lbs):

Each liter (33.8 oz) of water weighs almost exactly one-kilo

A 15L day-pack, with 2 cliff bars, your keys, a spare inner tube, and cell phone

2 cans of 16-oz craft beer

6 to 7 apples

Losing weight is the easiest and fastest way to increase PWR for most recreational mountain bikers. However, gaining strength while keeping your weight the same (or less) is also an effective way to get stronger on the bike and power up those hills easier.

So what are some ways to get stronger?

Weight-train: Squats, deadlifts, lunges, pushups, pull-ups, jumps

High-Intensity-Interval-Training (HIIT): Mountain biking is HIIT. However, if the only time you’re actually performing a HIIT style “workout” is while riding, then it’s time to incorporate a training regime into your routine. Think CrossFit, Cardio Kickboxing, or any training where you go all-out followed by short active recovery periods….and repeat.

2) Get bigger tires

“29er “rolls over” obstacles more easily requiring

less energy to ride”

There is a reason that 26 inch tires have fallen out of style…..27.5 and 29ers a just better.

“29-inch wheels showed a clear performance advantage during hill climbs”

A 2017 study, from Southern Utah University, examined energy expenditure during singletrack riding between 26ers and 29ers. The results:

During uphill riding, 29ers had ~7% faster times and speeds with over 10% lower caloric expenditure

29-inch wheels (29ers) hold their momentum over a combination of terrain, which means those bigger tires make it easier to maintain speed over obstacles

A 2016 study titled, The Effect of Mountain Bike Wheel Size on Cross Country Performance, studied the performance differences between 26ers, 27.5, and 29ers on a singletrack course.

The researchers’ conclusion:

“The findings indicate that wheel size does not significantly influence performance during cross-country when ridden by trained mountain bikers, and that wheel choice is likely due to personal choice or sponsorship commitments”

-Journal of Sports Sciences

It should be noted that although the researchers didn’t “find” any “significant” differences between the three types of MTBs, there was a clear cut winner.

“Athletes rated the 29“ bike significantly better than the 26“ bike for rolling over obstacles such as roots, for having better traction and for performance in general”

The study course was only 2 miles long (3.5km), yet the 29ers averaged 12 seconds faster than the 26ers and 21 seconds faster than the 27.5 MTBs.

The researchers also stated in this same study, “over a full race distance with multiple laps, indicate “29” wheels may potentially offer a greater advantage over smaller wheel sizes.”

I’m often curious when I read the conclusion section of academic studies, and how the researchers come to their conclusions. Understanding the difference between “significant” in laboratory settings and “significant” in the real-world is not the same. For ANY mountain bicyclist, expending 9.2% less energy while riding a 29er uphill is SIGNIFICANT.

Actual results from this same study

The 29er requires 9.2% less energy to climb a hill compared to 27.5

29ers used 6.7% less effort than the 26ers

What about TIRE WIDTH?

Few studies have researched the width of MTB tires. However, the few studies that have been conducted, under real single-track conditions, find that wider tires equal better.

Wider tires = increased efficiency (holds momentum better)

Rolling Resistance between narrow & wide tires is nearly identical (assuming both are rolling at a normal PSI)

Fewer Vibrations: Wider tires dampen obstacles & uneven ground. While this isn’t a direct advantage of uphill climbing, it does make mountain biking more fun and less fatiguing overall

Wider tires are heavier, and if running at low-PSI are harder to propel forward. As with most things, bigger is better……up to a point. Finding the“sweet spot” is dependent on your height & weight, riding style, and what type of terrain you bike.

3) Clean bike & drivetrain

The bicycle drivetrain at a maximum is 98.6% efficient. However, that’s under perfect laboratory conditions, which don’t exist outside. Once your drivetrain has been beaten down by the elements, dirt, grime, or worn teeth, you’re transmission isn’t even performing at 75% efficiency.

Cleaning & lubing chain after a ride

Hitting the trails with a clean and properly lubed chain will make climbing easier, as your not wasting energy with each pedal stroke.

Also, having a clean bike rides faster. Switching gears is easier and more efficient, and for all the upgrades that cost hundreds of dollars to save a few ounces, a half-gallon of caked-on, dried up mud weighs in at about 3 pounds (fresh mud is much heavier), which will add minutes to a short, multi-loop ride.

4) Get a shorter crank arm

When you are climbing uphill, trail obstacles such as rocks, roots, and logs will slow you down and cause you to lose momentum. A shorter crank arm allows you to reach peak power significantly faster. In addition to shorter crank arms producing power faster, they also produce more peak power, and have a higher ground clearance, which will help you clear trail obstacles.

So what size crank arm is best?

No bigger than 170 mm

170 mm crank arm is ~22% faster in reaching maximum power output compared to 175 mm and 8% faster than 172.5 mm

“The decreased time to peak power with the greater rate of power development in the 170 mm condition suggests a race advantage may be achieved using a shorter crank length than commonly observed”

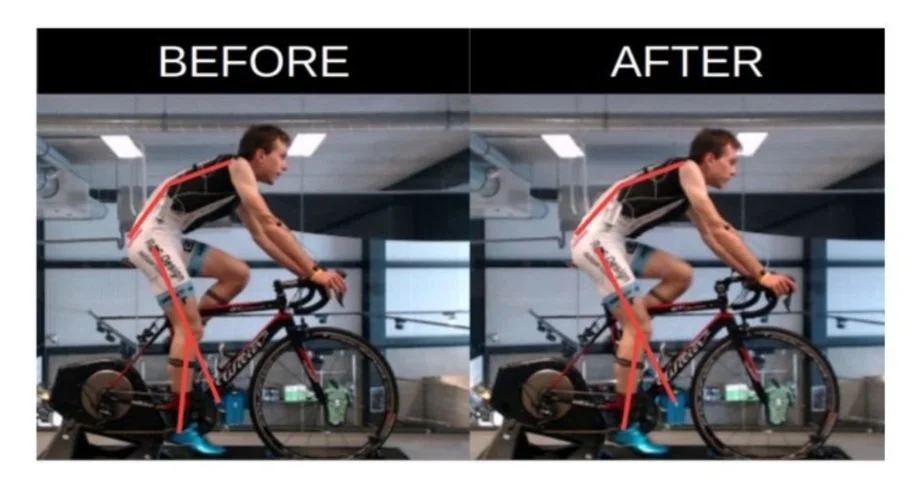

5) Ride with a dropper post & maximize STA

While most people associate the benefits of a dropper post while descending, there are benefits to having a dropper post while climbing.

“The angle between the seat tube and ground is the most important angle on the bicycle frame ”

Most cyclists keep their MTB seat lower than their road bike saddle. Riding with your saddle just 1-inch (25 mm) below optimal height reduces your maximum power by ~4 to 8%, with further reductions as you lower your saddle.

Also, keep in mind that as you lower and raise your seat, you’re effectively altering your Seat Tube Angle (STA). You can also change your STA by sliding the seat forward or back.

Seat Tube Angle (STA) of 72°, this STA mimics “shallow” frame geometry and STA of 82°, which mimics “steep” frame geometry.

Image & Caption Source: (Ricard et al., 2006)

A more forward sitting saddle is good for climbing

A “steeper” STA is more mechanically efficient. Generally, studies don’t show an increase in power output with a steeper angle but show a reduction of energy expended while generating the same power

A forward sitting saddle is known as “steep,” since the angle increases or “steepens”

The ability to adjust your seat on the go during the entire duration of your ride will do wonders for both your climbing and flying.

6) Don’t get intimated by “the hill”

20º hill (Image Source: Stefanucci et al., 2005)

“As has been shown in previous studies, participants grossly overestimated the slant of the hill ”

Bicyclists hugely overestimate the steepness of hills, especially when tired.

The hill in the above picture has a 20º slope. The average cyclist would estimate this slope to be 40º when fresh, and over 60º when tired.

Illustration of an alternative account of bicyclist hill misperception based on postural adaptation after extended riding: If one adapts to a lowered head or gaze posture while biking (or hiking), one may misperceive slightly downward gaze as being forward gaze. The image in the bubble represents the perceptual error in geographical slant (increased overestimation) predicted based on a misperception of gaze direction (dashed line) relative to the true straight ahead. Image & Caption Source: (Durgin et al., 2012)

“Hills do, in-deed, look steeper when we are tired than when we are not”

Studies also show that hills appear steeper to tired and fatigued bikers. Not because of low blood sugar or dehydration, but because of perception. As you become fatigued, your posture changes, thus altering your line of sight. As your tired eyes focus more on the ground, when you do look ahead, the hills appear much steeper.

When you attack hills, look ahead and not down. Also, most hills on singletrack trails are not above a 15% gradient. Don’t let your mind trick you into thinking it’s a 30% slope because it’s not, and thoughts like that will only slow you down.

Jesse is Director of Pedal Chile and lives in Valdivia, Chile (most of the year). Jesse has a Master of Science in Health & Human Performance and is an avid MTBer, snowboarder, reader of narrative non-fiction, taster of craft beers, and goat-like climber on a bike or hike.

More Articles from PEDAL CHILE

Sources

Durgin, F.H., Klein, B., Spiegel, A., Strawser, C.J. and Williams, M. (2012). The social psychology of perception experiments: Hills, backpacks, glucose, and the problem of generalizability. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 38(6), pp.1582–1595.

Hurst, H.T., Sinclair, J., Atkins, S., Rylands, L. and Metcalfe, J. (2016). The effect of mountain bike wheel size on cross-country performance. Journal of Sports Sciences, 35(14), pp.1349–1354.

Macdermid, P.W. and Edwards, A.M. (2009). Influence of crank length on cycle ergometry performance of well-trained female cross-country mountain bike athletes. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 108(1), pp.177–182.

Proffitt, D.R., Bhalla, M., Gossweiler, R. and Midgett, J. (1995). Perceiving geographical slant. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 2(4), pp.409–428.

Ricard, M. D., Hills-Meyer, P., Miller, M. G., & Michael, T. J. (2006). The effects of bicycle frame geometry on muscle activation and power during a wingate anaerobic test. Journal of sports science & medicine, 5(1), 25–32.

Stefanucci, J.K., Proffitt, D.R., Banton, T. and Epstein, W. (2005). Distances appear different on hills. Perception & Psychophysics, 67(6), pp.1052–1060.

Steiner, T., Müller, B., Maier, T. and Wehrlin, J.P. (2015). Performance differences when using 26- and 29-inch-wheel bikes in Swiss National Team cross-country mountain bikers. Journal of Sports Sciences, 34(15), pp.1438–1444.

Taylor, J., Thomas, C. and W. Manning, J. (2017). Impact of Wheel Size on Energy Expenditure during Mountain Bike Trail Riding. International Journal of Human Movement and Sports Sciences, [online] 5(4), pp.77–84.

Wood, B.M. and Albrechtsen, S.J. (2008). Power Development in Hill Climbing as a Function of Bicycle Weight. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 40(Supplement), p.S42.