“This study appears to debunk the general belief among cyclists and the cycling industry that the stiffest cycling shoe soles yield the highest performance.”

Cycling shoes are designed to be light, snug, and stiff. The element of stiffness, allows you to transfer force efficiently from your foot to the pedal since stiff shoes flex or bend less.

Stiffer soles make pedaling more efficient as more of the energy is transferred from your foot to the pedal but only during sprints and periods of all-out cycling. Recreational riding doesn’t generate enough force onto the pedals to cause sufficient shoe deformation and the low cadence doesn’t affect muscle coordination.

While stiff-soled cycling shoes have been shown to improve performance, studies show that increasing the level of stiffness even further doesn’t make you faster, and can exacerbate pain, numbness, tingling, burning, and discomfort in your feet due to the increased pressures.

Cycling performance: Stiff shoes & Science

Product designers and manufacturers say:

“The stiffer the sole, the better the transfer of power through the pedals and better performance.”

However, finding scientific evidence to actually substantiate these claims is rather challenging. A 2020 study entitled “No effect of cycling shoe sole stiffness on sprint performance” concluded:

"In conclusion, we found no difference in performance between less stiff and stiffer road cycling shoe soles during short uphill sprints in recreational/competitive cyclists. The stiffest cycling shoe soles showed no performance benefits in: 50 m average and peak 1-second power, average and peak change in velocity, maximum velocity, peak acceleration, or peak torque compared to a moderately stiff and the least stiff road cycling shoe soles offered by a well-known manufacturer." (bolding is mine)

-----(Hurt and Kram, 2020)

This most recent study confirms what has been known since the 1990s, which is that stiffer soles are better than flexible running shoes, but stiffer is only better up to a point.

The aforementioned study tested 3 different cycle specific shoes of varying stiffness during a 50 meters sprint up a 5% hill and blinded the shoes by covering all logos and graphics and by matching the uppers.

The stiffness index and materials of the 3 cycle-shoes:

6.0 stiffness index - Injection-molded nylon composite

8.5 stiffness index - carbon fiber/fiberglass composite blend

15.0 stiffness index - Carbon fiber sole

One of the questions that this paper was unable to answer is what is the “critical” sole stiffness where performance worsens.

If this question could be answered, then manufacturers could develop a shoe that would optimize comfort and performance. The stiffer the sole, the more unnatural it becomes, and uncomfortable.

Performance Benefits: Hills & Sprints

Stiffer shoes only offer performance benefits while pedaling all-out, such as during hill climbs, sprints, and fast accelerations.

Sub-maximal pedaling, such as recreational riding at a comfortable pace, stiff-soled cycling shoes don’t perform any better than comfy athletic sneakers.

Cycling Shoes: Maximum effort sprints & hill climbs

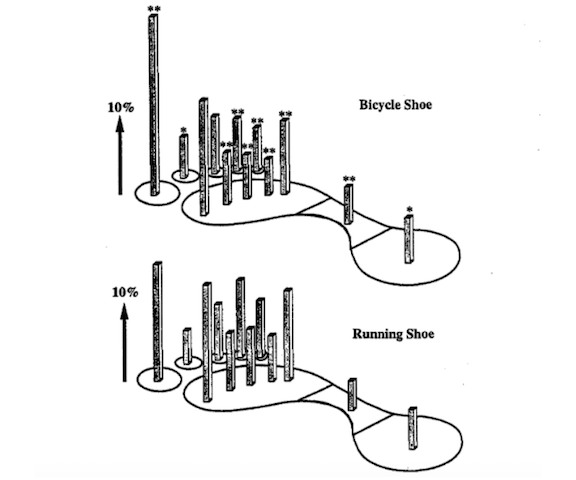

Stiff soled cycling shoes outperform regular sneakers during all-out sprints:

10% more power output with cycling shoes compared to regular shoes (even less with a stiffer soled rubber shoe)

The level of stiffness of cycle-specific shoes does not correlate with performance

Some stiff cycling-shoes perform worse than more flexible ones and vice-versa as the function of shoes is much more than just stiffness

The difference between the least stiff cycling shoe to the stiffest is about .6 watts more power in the stiffest.

Flexible Shoes & Wasted Energy

In running, your shoe can actually store energy and return it as elastic energy.

Cycling, by contrast, any mechanic energy that deforms the shoe during the downstroke is lost during the upstroke. However, the difference in this “lost” energy is about .6 watts between the least stiff to stiffest cycle-specific shoe since the relative difference in stiffness is “modest” to say the least.

Considering many cyclists produce 1000+ watts during sprints, the difference between sole types is less than 0.1% or less than 1/10 of a percent.

Ricardo’s cycling shoes (Pedal Chile guide)

Cycle Shoes: comfort vs Stiffness

“Competitive or professional cyclists suffering from metatarsalgia or ischemia should be especially careful when using carbon fiber cycling shoes because the shoes increase peak plantar pressure, which may aggravate these foot conditions. ”

Cycle-specific shoes, especially when riding clipless, is one of the most important pieces of gear since your feet will be attached to the bike the entire ride. Proper and comfortable fitting shoes is more important than the level of stiffness.

Cycling-specific shoes are stiffer than sneakers or athletic shoes, and this stiffened sole spreads out pedal forces more evenly across the foot. In running shoes, most of the force from pushing into the pedal is centered around the toes/ball of foot, whereas in cycling shoes, the pressure is more evenly distributed.

On a continuum from super flexible to super-rigid shoes, the perfect comfort level for cyclists is somewhere in the middle and based on numerous other factors. A shoe too flexible, like sneakers, places too much pressure on the balls of your feet. However, too stiff a sole, combined with a less-than-perfect fit, will lead to high hallux (big toe) pressure, which can magnify pain, numbness, tingling, and burning in your feet.

"Somewhat less stiff cycling shoe soles may help to prevent or alleviate metatarsalgia or ischemia that can occur in cyclists due to the increased plantar pressures associated with carbon fibre cycling shoe soles." -(bolding is mine)

-----(Hurt and Kram, 2020)

Cyclists who ride clipless pedals are 2 to 3 times more likely to experience foot pain compared to riders who use platform pedals. The cycling shoe is supposed to alleviate foot pain, not exacerbate it.

This makes you wonder if cycling shoes have gotten too stiff over the years, as studies show that the stiffest of shoes can lead to foot pain and discomfort.

why are clipless shoes so stiff?

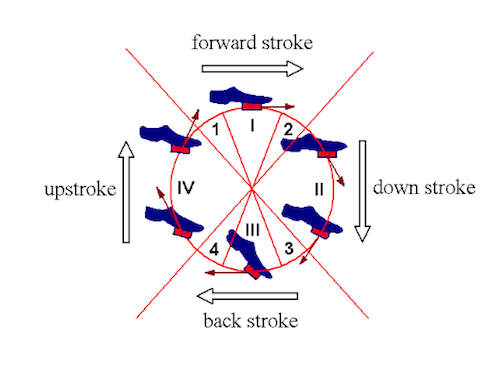

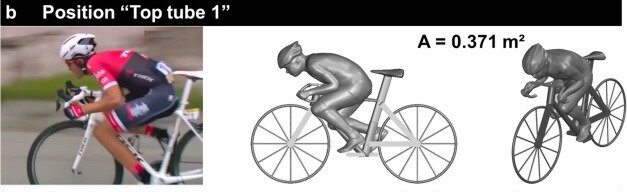

(Image Source: Stępniewski and Grudziński)

Why are clipless shoes so stiff?

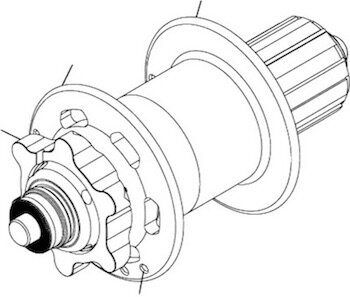

Platform pedals or flat pedals provide a large “platform” that you can drive into.

Clipless pedals, however, are small and require a much stiffer shoe to disperse the pedaling force as the connection area is 80% smaller than a flat pedal. Because of this reduced area, the soles of the shoe itself becomes the platform. If the shoe wasn’t stiff, you would be driving your foot into a tiny area, which would be uncomfortable and inefficient.

“Just because something makes you faster doesn’t make it better ”

Clipless pedals are stiffer than traditional shoes because they have to be.

Even if super stiff shoes facilitated a more efficient transfer of power and thus made you faster, it still doesn’t mean that stiffer is better. Discomfort, pain, and injuries are all exacerbated from pedaling with a super stiff shoe. While it makes sense to wear the fastest shoe on race day, recreational riding and training sessions are a different story.

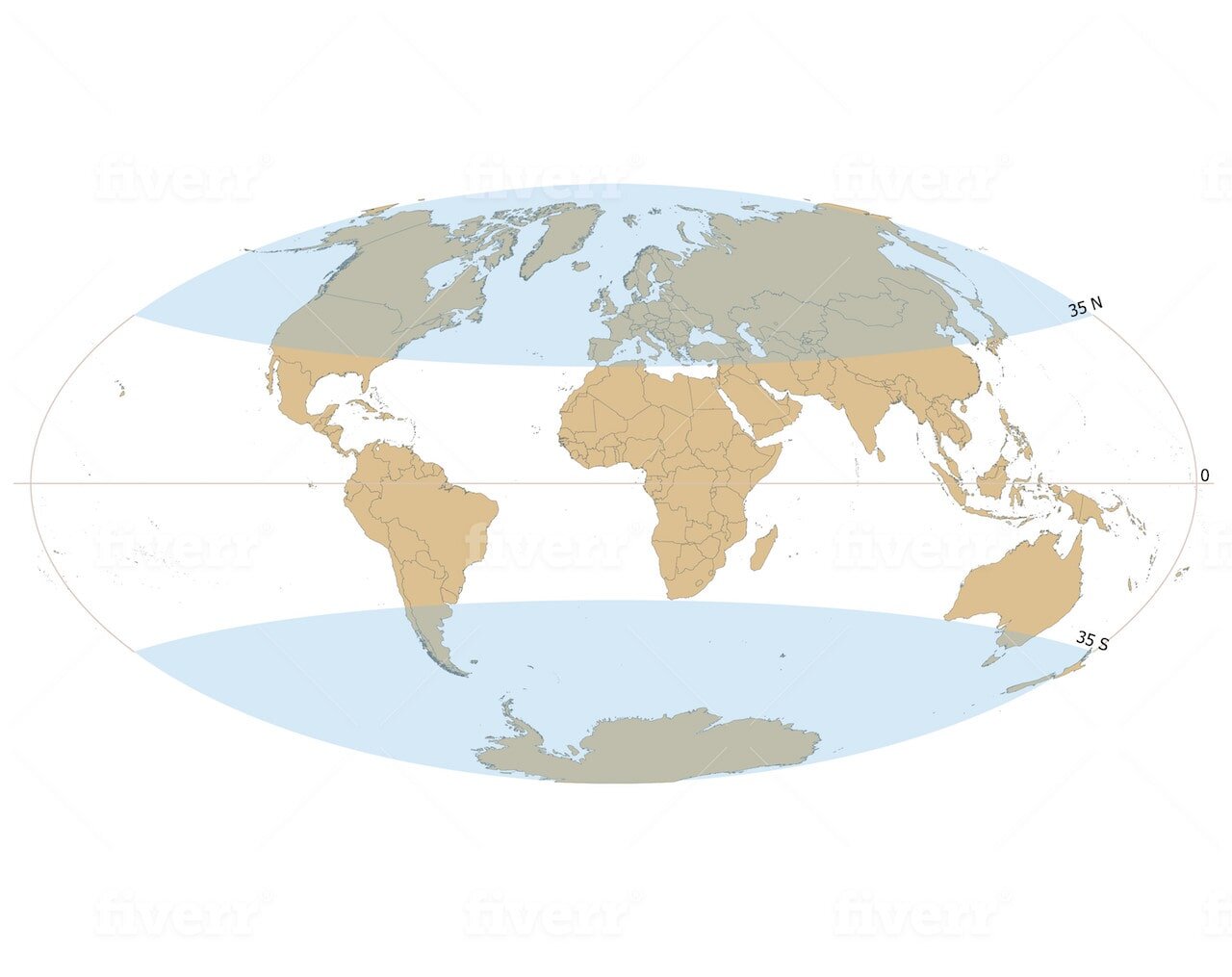

Track Cycling & Smaller Pedals

Track (sprint) cyclists benefit from clipless pedals more than any other cycling discipline.

The original LOOK clipless pedal system was nearly the same size as standard flat pedals. To avoid contact between the pedal and the steep banking track, designers made the pedal smaller and more compact. As high strength materials were developed, the pedal sizes became even smaller. Also, faster accelerations was a side effect of this, due to the reduced pedal mass.

Final Thought

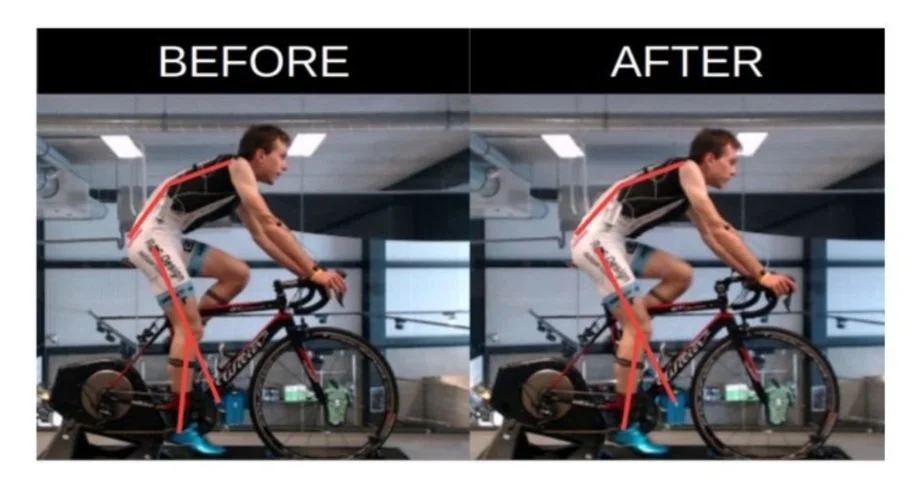

If you’re wanting to go faster, there are less expensive and easier ways, for example:

Shaved legs = 50 to 82 seconds faster over 25 miles (40km)

Shaved arms = 13 to 22 seconds faster over 25 miles (40km)

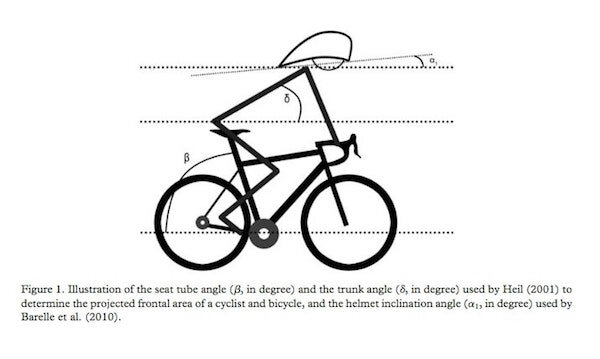

Change your riding posture = seconds to minutes over same distance

Jesse is the Director of Pedal Chile and lives in La Patagonia. Jesse has a Master of Science in Health and Human Performance and a Bachelor of Science in Kinesiology. Hobbies: Mountain biking, bicycle commuting, reading, snowboarding, researching, and sampling yummy craft beers.

Sources & references for stiffer soles and bicycle performance:

Burns, Andrew C., and Rodger Kram. “The Effect of Cycling Shoes and the Shoe-Pedal Interface on Maximal Mechanical Power Output during Outdoor Sprints.” Footwear Science, vol. 12, no. 3, 24 May 2020, pp. 185–192.

FastFitnessTips: Cycling Science. “Are Carbon Soles on Cycling Road or Mtb Shoes Worth It?” YouTube, 9 Nov. 2019, www.youtube.com/watch?v=fzZT0wgIzNI.

Fletcher, Jared R., et al. “The Effect of Torsional Shoe Sole Stiffness on Knee Moment and Gross Efficiency in Cycling.” Journal of Sports Sciences, vol. 37, no. 13, 18 Jan. 2019, pp. 1457–1463.

Global Cycling Network. “Clipless Pedals Vs Flat Pedals - Which Is Faster? | GCN Does Science.” YouTube, 23 July 2017, www.youtube.com/watch?v=AkMCYYNTWUY&t=461s.

Hennig, Ewald M., and David J. Sanderson. “In-Shoe Pressure Distributions for Cycling with Two Types of Footwear at Different Mechanical Loads.” Journal of Applied Biomechanics, vol. 11, no. 1, Feb. 1995, pp. 68–80.

Hurt, James W., and Rodger Kram. “No Effect of Cycling Shoe Sole Stiffness on Sprint Performance.” Footwear Science, 4 Oct. 2020, pp. 1–9.

Jarboe, Nathan Edward, and Peter M. Quesada. “The Effects of Cycling Shoe Stiffness on Forefoot Pressure.” Foot & Ankle International, vol. 24, no. 10, Oct. 2003, pp. 784–788.

Koch, M., Frohlich, M., Emrich, E., & Urhausen, A. “The impact of carbon insoles in cycling on performance in the Wingateanaerobic test.” Journal of Science and Cycling, vol 2, no. 2, 30 Dec. 2013, pp. 2 - 5.

“Pedal, Left, Accessories, Shuttle Cycle Ergometer.” Smithsonian Institution.

Sanderson, David J., et al. “The Influence of Cadence and Power Output on Force Application and In-Shoe Pressure Distribution during Cycling by Competitive and Recreational Cyclists.” Journal of Sports Sciences, vol. 18, no. 3, Jan. 2000, pp. 173–181.

Stępniewski, A.A., and J. Grudziński. “The Analysis of Pedaling Techniques with Platform Pedals.” International Journal of Applied Mechanics and Engineering, vol. 19, no. 3, 1 Aug. 2014, pp. 633–642.

Uden, H., Jones, S., & Grimmer, K. (2012). Foot Pain and Cycling: a survey of frequency, type, location, associations and amelioration of foot pain. Journal of Science and Cycling, 1(2), 28-34.