When does walking become more efficient than cycling uphill?

Road cycling: The "critical slope" or the incline where walking (or running) becomes more efficient than cycling is 13–15% (recreational cyclists)

Mountain Biking: The “critical slope” is 8 - 11% before it becomes more efficient to walk then to continue pedaling.

Walking uphill is approximately 35% more energy efficient compared to cycling up the same hill.

20º/36% Hill (Image Source: Stefanucci et al., 2005). It’s significantly easier to walk up this hill

Cycling on flat ground with no wind is about 4 times more efficient than walking. The keyword in the previous sentence is “flat.” Once you start pedaling up a hill, even a small one, you might find yourself being passed by a walker.

A hill with only a 4% gradient will slow a cyclist down by 75%, while the same hill will slow a walker down by 38% at the same power output.

Why is cycling uphill harder than walking uphill?

Even a small hill can feel like a mountain. (Riding with my friend Josh in DuPont…or in this situation….walking)

“Cycling uphill is merciless, and it immediately has an enormous impact on your body. Your breathing and heart rhythm react to the smallest slope percentage.”

When cycling on flat terrain the two main opposing forces are rolling resistance (energy loss between wheels and surface) and air resistance. Once you are pedaling uphill, gravity becomes the main resistance.

Why cycling uphill is harder than walking:

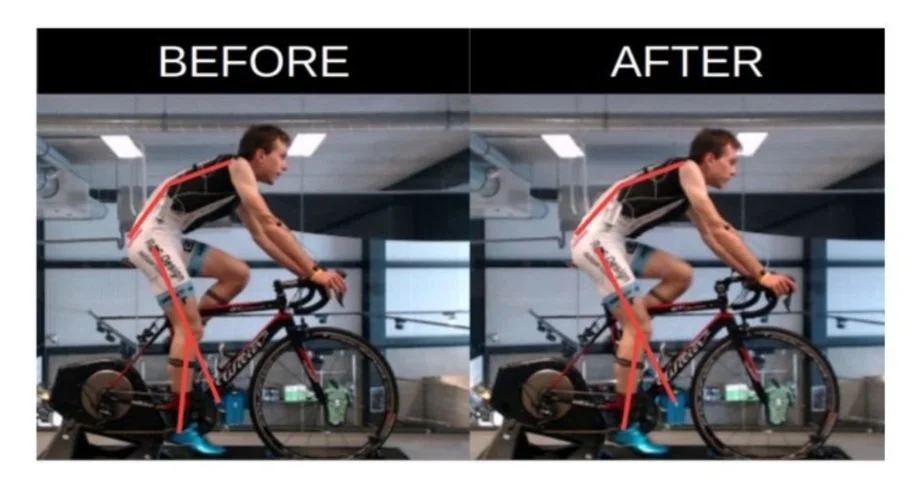

Image Source: (Fonda and Sarabon, 2012)

Holding torque on the pedals - Especially during the cranks dead center, cycling required constant torque on the pedals. Walking, by contrast, there is a pause between each step.

Weight of the bicycle - You need to overcome gravity with the additional weight of the bike.

Gearing - Most bikes, even in the lowest gear, are still too challenging. This equates to a sub-optimal cadence rate, resulting in a ~25% loss of pedal efficiency.

Altered walking/running mechanics during uphill climbing - As flat ground turns into hilly terrain, you will automatically take faster steps. Also, you change which part of your foot makes contact with the ground. Both of these changes result in increased activation of your calf, butt, hamstrings, and hip muscles.

“walking uphill is slightly more efficient (in terms of energy consumption) than level walking ”

Cycling uphill also changes biomechanics. However, the changes in posture generally make cycling less efficient. Cyclists have to adjust weight forward to keep the front wheel on the ground while stabilizing the body from sliding around in the saddle.

uphill climbing & mountain biking

“This is more pronounced in MTB where larger tires, unpredictable terrain and repeated climbs due to the circuit nature of MTB requires MTB cyclists to exert significant effort against gravity ”

Taking the gondola up in Telluride…..”slightly” easier than MTBing uphill

Mountain biking uphill is harder compared to road cycling.

While cycling uphill on the road, the primary resistance is gravity.

Mountain biking uphill, you have to battle gravity…..and more of it, plus rolling resistance, tire deflection, and loss of momentum from hitting trail obstacles, such as rocks, logs, stones, and roots.

Mountain bikes also have larger tires that are rolling at a lower PSI, with variable terrains, such as gravel, sand, mud, clay, and dirt, all conditions that make wheels turn slowly.

The dual suspension, dropper post, thru-axles, disc brakes, and larger tires, all add weight to MTBs, making them even more inefficient uphill.

“Apart from the tyre, the current 29-in. wheels seem to offer lower rolling resistance (by up to 23%) than the previous 26-in. wheels, resulting in a speed increase of 2–3%”

How much harder is it to pedal a bike with “fat tires” compared to a road bike?

Most things being equal (speed, gradient, tire pressure, etc.) it takes nearly 19% more energy to ride a fat tire bike compared to a road bike.

METS & uphill Cycling vs walking

Continuum of physical activity - (Image Source: Thosar, Saurabh S et al.)

METS or Metabolic Equivalent of Task is the measure of the ratio of the rate at which a person expends energy of a specific task relative to what you would expend while sitting quietly. Walking uphill at 3.5 mph equates to 6 METS. Which means this activity requires 6 times more oxygen compared to just sitting down chilling in a chair.

Brisk walking at 3.5 mph on a level ground = 3.8 METS

Walking uphill at 3.5 mph = 6 METS

Climbing (walking) uphill with 40-pound backback = 9METS

Cycling uphill = 10 to 16 METS

Jesse (Director of Pedal Chile) lives in Chile’s Patagonia (most of the year). Jesse has a Master of Science in Health & Human Performance and a Bachelor of Science in Kinesiology. Hobbies: Mountain biking, reading, researching, sampling craft beer, and mountain biking uphill.

Sources

Ardig, L.P., Saibene, F. and Minetti, A.E. (2003). The optimal locomotion on gradients: walking, running or cycling? European Journal of Applied Physiology, 90(3–4), pp.365–371.

The Compendium of Physical Activities Tracking Guide. (n.d.). [online]

Fonda, Borut & Sarabon, Nejc. (2012). Biomechanics and Energetics of Uphill Cycling: A review. Kinesiology. 44. 5-17.

Fonda, B., Panjan, A., Markovic, G. and Sarabon, N. (2011). Adjusted saddle position counteracts the modified muscle activation patterns during uphill cycling. Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology, 21(5), pp.854–860.

Impellizzeri, F.M., Ebert, T., Sassi, A., Menaspà, P., Rampinini, E. and Martin, D.T. (2007). Level ground and uphill cycling ability in elite female mountain bikers and road cyclists. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 102(3), pp.335–341.

Maier, T., Müller, B., Allemann, R., Steiner, T. and Wehrlin, J.P. (2018). Influence of wheel rim width on rolling resistance and off-road speed in cross-country mountain biking. Journal of Sports Sciences, 37(7), pp.833–838.

Stefanucci, J.K., Proffitt, D.R., Banton, T. and Epstein, W. (2005). Distances appear different on hills. Perception & Psychophysics, 67(6), pp.1052–1060.

Thosar, S. S., Johnson, B. D., Johnston, J. D., & Wallace, J. P. (2012). Sitting and endothelial dysfunction: the role of shear stress. Medical science monitor : international medical journal of experimental and clinical research, 18(12), RA173–RA180. https://doi.org/10.12659/msm.883589

Van Den Bosch, P. (2006). Cycling for triathletes endurance. Oxford Meyer & Meyer Sport.

Vernillo, G., Giandolini, M., Edwards, W.B., Morin, J.-B., Samozino, P., Horvais, N. and Millet, G.Y. (2016). Biomechanics and Physiology of Uphill and Downhill Running. Sports Medicine, 47(4), pp.615–629.

Wilson, David (2004). Bicycling science. Cambridge (Massachusetts): Mit Press.

Wilson, David (2020). Bicycling Science. S.L.: Mit Press.